polar zones

The planet’s polar zones, while covering approximately the same area, are really very distinct: the Arctic is water-based, the Antarctic land-based. The northern zone consists of the world’s smallest ocean, the Arctic Ocean, with an ever-fluctuating floating coverage of sea ice ranging from a few centimetres to around two metres in thickness over its 14 million square kilometre expanse, all but surrounded by land (Europe, Asia and North America) and connected to the Atlantic and Pacific ocean basins. Antarctica is a 14.2 million square kilometre landmass, 98 % of which is covered by ice up to 4,700 metres thick, surrounded by the Southern Ocean. The average annual temperature at the South Pole is -49.3 °C, while at the North Pole it is -18°C. From an economic and political perspective the two poles are also far apart: the Arctic faces many jurisdictional issues with overlapping claims for extended continental shelves (if approved by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf) between Canada and the USA; Canada, Denmark and the Russian Federation; and Norway and Denmark. In the Antarctic, the Antarctic Treaty puts all jurisdictional claims aside, side-stepping any delimitation disputes, while the Rules of Procedure of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf preclude the Commission from examining any claims in the region. From an economic perspective, while fish stocks are of interest in both polar regions, in the Arctic hydrocarbons (30% of the world’s undiscovered oil and 13% of gas is believed to be located there), lead, zinc, iron and rare earth minerals are of additional interest.

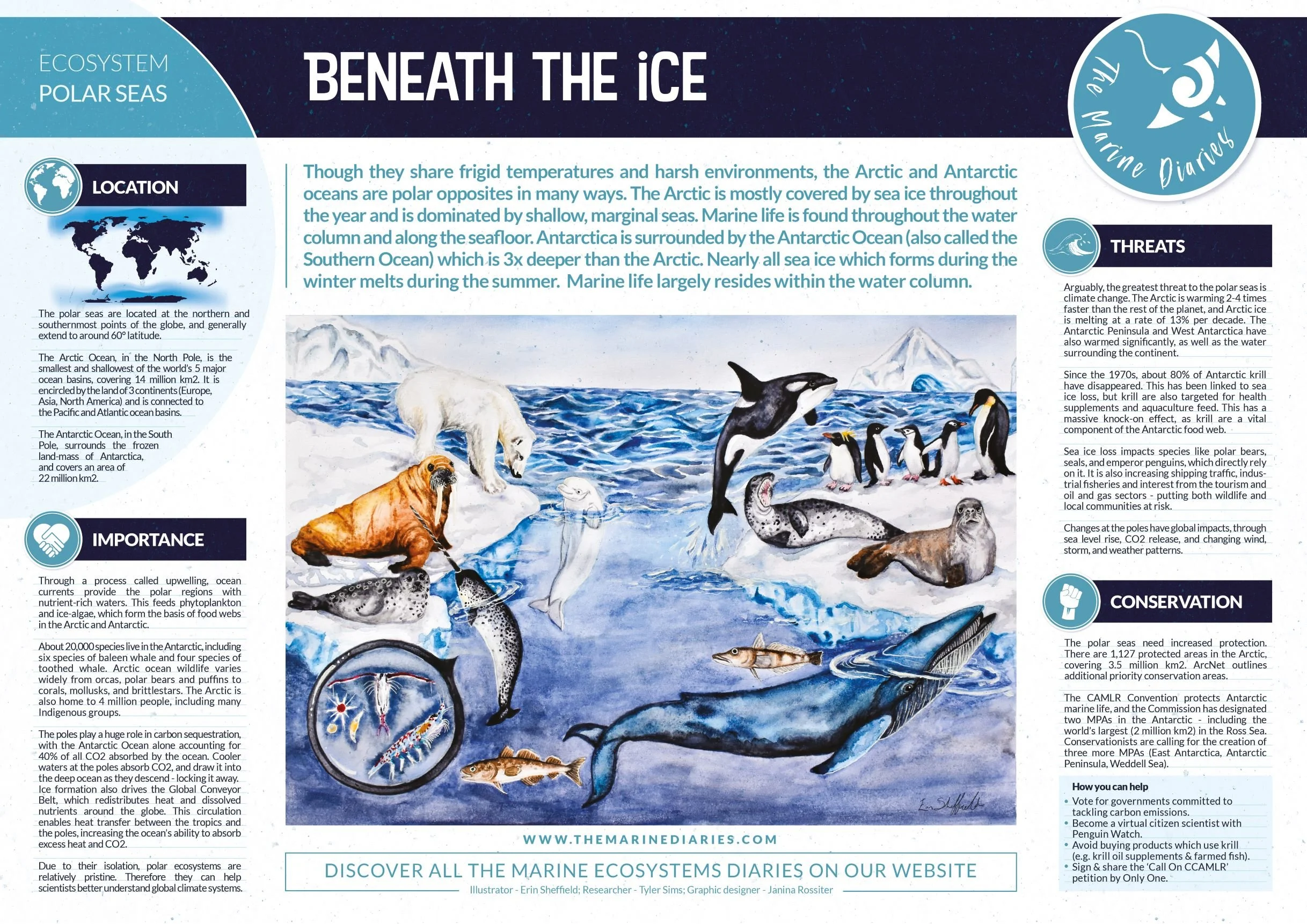

Similarities do of course exist: both ecosystems see the seasonal fluctuation in the formation and melting of the sea ice, which effects the availability of nutrients: as the ice melts these are released, feeding phytoplankton, the foundation of the marine food chain and providing nutrition for numerous species, from krill to the whales who feed on them.

Both poles are also massively under threat from climate change. As the sea ice in the Arctic recedes and as glaciers carve into the Southern Ocean, the area available to reflect the solar radiation from the sun is reduced. Instead, the heat is absorbed by the dark ocean waters, leading to a further temperature rise. If we only succeed in limiting climate change to 2 °C rather than 1.5 °C this means that it will be ten times more likely that the summers will be free from any sea ice.

We have already lost over 40% of the Arctic sea ice since satellite coverage began in the 1970s - with the current rate of ocean warming, where the Arctic is warming three times faster than the rest of the planet, there will be no summer sea ice in the Arctic by 2035. An ice-free Arctic Ocean will allow for more traffic in the region as container ships take advantage of far shorter routes (the Northern Sea Route, the Northwest Passage, the Transpolar Sea Route and the Arctic Bridge), saving up to 16 days in the journey from Asia to Europe. In addition to higher levels of shipping and the inevitable pollution that accompanies it, the unsustainable exploitation of resources is a further threat to the Arctic as interest in polar resources increases, from fishing in ice-free waters to oil and gas exploitation.

Both poles also play a critical role in carbon sequestration, about 40% of the CO2 absorbed by the ocean is taken up in the Antarctic alone. Thermohaline circulation, sometimes called the ocean conveyor belt, transfers water, heat, oxygen, carbon, salt, nutrients and pollution around the planet from the surface to the ocean depths, from the poles to the Equator, helping to balance the global climate and playing a key role in the hydrological cycle. It takes about a thousand years for one loop of the belt to be completed. CO2 is absorbed at a higher rate by the cooler waters at the poles, the downwelling which occurs there locks the carbon into the deep ocean. Climate change is slowing this down: as CO2 emissions increase, the ocean temperature rises and sea ice melts, with more freshwater entering the ocean at the poles, the salinity and therefore density of the water is reduced, meaning that the downwellings at the poles are also reduced. This slows the thermohaline circulation and reduces the ocean’s capacity to absorb more CO2, meaning that more CO2 will enter the atmosphere, causing ocean temperatures to rise faster, sea ice to melt faster, thermohaline circulation to slow further, and the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide to diminish further.

Protecting the polar regions

A protective regime exists for the Antarctic in the shape of the Antarctic Treaty, signed in Washington on 1 December 1959 by the 12 countries whose scientists had been active in and around Antarctica during the International Geophysical Year of 1957-58. It entered into force in 1961 and now has 54 parties. The Treaty includes strong protocols to protect the natural environment for the benefit of present and future generations, indefinitely bans all mineral resource exploration, mining and drilling and prohibits military activities. The Protocol on Environmental Protection of 1991 (known as the Madrid Protocol) bans mining in Antarctica indefinitely, designating the continent as a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science”.

The area gains from further protection through the work of the commission of the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), an international treaty adopted at the Conference on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources which met in Canberra, Australia, in 1980. The Convention established a commission and a scientific committee, charged with the protection of marine life in the Antarctic. According to its website, CCAMLR’s main achievements are:

addressing the challenge of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing;

establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean;

reducing seabird mortality;

establishing the CCAMLR Ecosystem Monitoring Program (CEMP); and

managing Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (VMEs).

CCAMLR is trying to establish further MPAs in the Southern Ocean, including the Weddell Sea, East Antarctic and Western Antarctic Peninsula, all of which are currently being blocked by both China and the Russian Federation due to their economic interests in fisheries resources - in particular krill - in the areas.

No such legal regime exists for the Arctic. Instead, the Arctic Council, founded in 1996 with the eight bordering States as Members and many others as observers, promotes cooperation, coordination and interaction among the Arctic States, Arctic Indigenous peoples and other Arctic inhabitants on common Arctic issues, in particular on issues of sustainable development and environmental protection in the Arctic.

Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment is one of the key topics of the Council but resource exploitation is not banned, instead Guidelines are provided to the Arctic nations for offshore oil and gas activities during planning, exploration, development, production and decommissioning. The Arctic Council has no means to implement or enforce its guidelines, assessments or recommendations.

In light of an increase in polar traffic, whether for trade or tourism, the IMO established its IMO Polar Code which aims to regulate shipping in both regions, it covers the design, construction, equipment, training, search and rescue and environmental protection matters relevant to ships operating in the waters around the two poles. The Polar Code entered into force on 1 January 2017.

dive in deeper

Antarctic Avengers: All Eyes on Antarctica - June 2025

Only One’s collection of films on Antarctica: The Greatest Sanctuary

Treehugger: How does the Antarctic Treaty protect Antarctica?

Spotlight on the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition

The Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) was founded in 1978 to bring together the work of various conservation organizations involved in protecting the Antarctic and Southern Ocean ecosystems from the negative anthropogenic impact on the area. According to its website, it aims to protect the Antarctic environment (looking at tourism, shipping and biological prospecting), conserve Antarctic wildlife (with work on fisheries, whale sanctuaries, penguins and acoustic pollution) and play a role in Antarctic governance (made possible by its status as an official observer within the Antarctic Treaty regime). By providing research and policy advice, the coalition aims to assist members of the Antarctic Treaty regime in taking informed decisions, to report back to the environmental community on decisions taken there, and to raise awareness about key Antarctic conservation issues.

The coalition currently has three main topics of focus:

climate change: understanding the impact on the region as a matter of critical importance for both the continent and the whole planet;

preservation of the Ross Sea: by supporting the creation of a marine protected area in this area of rich marine biodiversity; and

conservation of krill: which plays a hugely important role as the base of the Antarctic marine food chain but faces growing demand as the Antarctic krill fishing industry expands.

ASOC calls on global leaders to "take another bold step towards Antarctic and Southern Ocean conservation by securing an agreement to adopt the East Antarctic, Weddell Sea, and the Antarctic Peninsula Marine Protected Areas."